The Silent Minority: Mexican-American Professionals: An Odyssey

An Odyssey in Search of Elusive Data

by Humberto Gutierrez

My Oh My, How Things Have Changed!

On a recent trip to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, I was very surprised to observe the differences in the city where I’d spent my high school and college years.

My memories of El Paso, Texas, and Juárez, Mexico, are negative. One reason is that what was then called Texas Western College and now is The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) was an institution where it was almost unknown for Mexican-Americans to join any fraternity. Now I find out that UTEP has a president who is Mexican-American. Similarly, my first cousin, who was voted out when she tried to join a sorority at Texas Western, is now the proud owner of a company and has received many local business honors.

There are many other dramatic changes in these two border cities since I lived there some 30 years ago. The minority back then–Mexican-Americans–is now the majority, yet there is so little research available on Mexican-Americans and how they are progressing. This is true in El Paso, Texas, and throughout the United States.

Most literature and research fails to segregate data on Mexican-Americans from that of all Latinos or Hispanics. Also, most literature and research describes only the poor segment of our Mexican-American community, though with good reason. They are most in need. According to the figures on California during the 1990s, “The income of a family of four in the lowest quarter of wage earners fell from $28,600 to $27,000 in constant dollars.”

But it is important to know more about the group of Mexican-American professionals who are and will be more and more influential in shaping the future of our society.

In Search of Statistics

A U.S. Census Bureau report dated March 2001 stated that “Among Hispanics, 66 percent were of Mexican origin. The country’s overall Latino population was close to 33,000,000 or 12 percent of our total population.” Some scholars are saying that the census 2000 figures show the

Hispanic population at 35.3 million, about 3 million more than that estimate.

Let me here remind the reader that the real human beings behind these numbers represent the entire spectrum of historical roots that one could imagine. At one end, you have the Mexican-American whose roots reach back to the arrival of Spanish explorers on this continent. A case in point is my stepfather’s nephew, a lawyer turned teacher. His grandmother’s last name was Flores. She was a native of Floresville, Texas, a small town near San Antonio named after her family during the early Spanish Exploration of North America. On the other end of the spectrum are the newly migrated Mexican-American professionals, about whom we know so little.

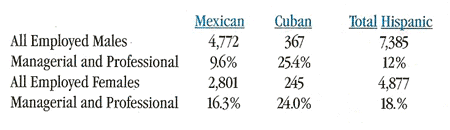

The chart shows numbers of employed Mexican-Americans and Cuban-Americans and the percentage of which are managers and professionals,as reported in the 1990 Census, by gender.

Employed Hispanic persons by occupation as percent of all employed Hispanic persons by sex, by type of Hispanic origin, 1990. The numbers represent thousands.

There are far fewer Cubans than Mexican-Americans, yet they are 25.4 percent of the Hispanic managers and professionals. It is also noteworthy that males outnumber females by a ratio of almost 2- to-1.

Similar data for 1985, for both sexes, shows Hispanics of Mexican origin as 5.1 percent of all Hispanics in “executive, administrative, and managerial occupations”; those of Cuban origin, 8.3 percent; Puerto Rican, 6.4 percent; and Other Hispanic, 7.0 percent.

We might conclude that 12 years ago, Mexican-Americans were the least likely to work in managerial or professional occupations, but with ground gained since 1985.

Some figures for the year 2000 Census are available, but thus far they refer to Hispanics and are not broken into subgroups. They show that “Hispanics are less likely than Non-Hispanic Whites to work in high-paying managerial and professional specialty occupations. In 2000, 14 percent of Hispanics

were in managerial or professional occupations compared to 33 percent of Non-Hispanic Whites. Eighteen percent of Hispanic women were in managerial or professional occupations, compared to 11 percent of Hispanic men.”

The proportions for Hispanics overall are similar to the figures from the 1990 Census for Mexican-American professionals–9.6 percent for men versus 16.3 percent for women and, for Hispanics, 11 percent for men and 18 percent for women.

Data made available on March 6, 2001, tell us that “the proportion of the Hispanic population age 25 and over with at least a bachelor’s degree ranged from 23 percent for those of Cuban origin to 7 percent for those of Mexican origin, according to survey data collected in 2000 and released… by the

Commerce Department’s Census Bureau.” There is a note of caution by the Census Bureau, to wit, these are estimates, collected in the March 2000 current population survey (CPS), and should not be confused with the Census 2000 results, which are scheduled for release over the next three years.

Checking the educational attainment of the Hispanic population, 25 years old and over, by type of origin, for the years 1985 and 1989, I found that for the Cuban population, there has been a steady rise in the percentage that have completed four years of college or more. In 1985, 13.7 percent of Cubans had at least a bachelor’s degree; in 1989, 19.8 percent; and in 2000, 23 percent. For

Mexican-Americans, 5.5 percent in 1985, 6.1 percent in 1989, and 7 percent in 2000, a slower rise for Mexican-Americans, but one must consider that Mexican-Americans represent a larger population. For example, in 1989, there were 790 Cubans with at least a bachelor’s degree, but at the same time, 5,931 Mexican-Americans with bachelor’s degrees. This does not mean that we should be content with what is obviously low representation of Mexican-Americans.

Mexican Stereotypes Holding Firm

Reviewing a report in The San Francisco Chronicle on the 2000 Census for information on professionals from Mexico, I read the following:

“…For immigrants who come from poor countries with scant educational opportunities, however, job prospects in the United States can be limited. Mexicans from rural areas, for example, lack an education that has kept up with changes in technology,” said Abdiel Onate, a professor of Latin American History at San Francisco State University…“They do all the menial jobs, here,” he said. “All the labor in the kitchens of the restaurants in the Bay area, installing telephones, landscaping, gardening, construction work. Without their labor, things would be much more expensive.”

This quote speaks for itself. There is little or no mention of Mexican-American professionals. There is still the focus on the stereotypical image of the Mexican-American as being uneducated.

The article does mention that Terry Alderete, vice president of Alameda County’s Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and chief of operations for the unity council, a community development agency, “has seen a wide range of new Mexican immigrants arriving in Alameda County over the past decade,

from day laborers to business people with capital to invest…”

No mention was made of education levels that would indicate Mexican-American professionals.

But an article in the Austin American Statesman; July 12, 2001, quoting a relevant study, said: “Mexican immigrants in the U.S. are better educated than widely believed, more urban, and increasingly more likely to settle in Texas than in California… [I]t challenges long-held stereotypes and is raising concerns in Mexico about a brain-drain flowing north…. [T]he migration of highly educated Mexicans ‘has a high cost for the development of Mexico, and their loss weakens all of society.’ ‘It implies the transfer of a valuable human resource, in which our country has made a substantial investment.’ About 6 percent of all Mexicans older than 20 who have college or postgraduate (SIC) degrees now live in the United States… Mexican demographers said the study’s findings confirm anecdotal indications that they have seen for years of migrant trends shifting from rural to urban and from unskilled to professional. They attributed the brain drain to Mexican oversupply meeting with U.S. demand.”

A Phoenix/Tucson Study

Dr. Ramona Ortega-Liston published in Public Personnel Management a very interesting article entitled “Mexican-American Professionals in Municipal Administration: Do They Really Lag Behind in Terms of

Education, Seniority, and On-The-Job Training?”

The related study took place in the cities of Phoenix and Tucson.

“Separation of data by ethnicity and nativity distinguishes this study from previous research that includes all Hispanics,” she wrote. “First, Mexican nationals were separated from Mexican-Americans. Second, Mexican-American professionals were separated from all other Spanishsurnamed ethnic groups. The need for separating data by ethnicity and nativity has been recommended…because it may yield a more accurate profile of each ethnic group on specific variables examined.” She should

be applauded for this great insight but gives credit in her footnotes to others who have advanced this strategy. She also concluded that at least for that study group in Arizona, “Mexican-American managers do not appear to lag behind on important career variables such as seniority, education,

and on-the-job training…”

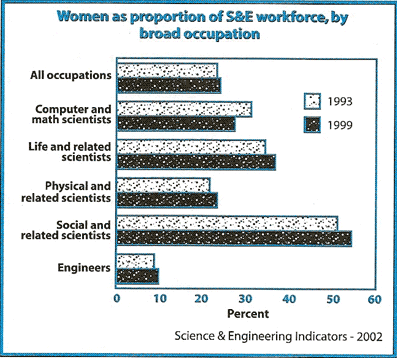

Science and Engineering

The National Science Foundation, in its Science and Engineering Indicators 2002, Vol. 2, reports that in 1999 there were 31,700 foreignborn (Mexican) U.S. residents with science and engineering degrees. This number does not include individuals with only foreign degrees who were not in the U.S. in 1990. Although this sounds like a great many, the total number of U.S. scientists and engineers in 1999 was 13,003,900. The total of foreign-born scientists and engineers is less than 1 percent.

The number of recipients of doctorates from U.S. universities who plan to stay in the U.S. and were born in Mexico remained steady, varying from 10 in 1996 to 11 in 1999.

There is no separate number for Mexican-Americans, but the total number of Hispanic science and engineering grads with earned bachelor’s degrees has grown from 9,268 in 1977 to 26,725 in 1999. Still a small fraction of the total science and engineering graduates.

By coincidence, Dr. Diana S. Natalicio, the president of my alma mater, the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), is a member of The National Science Board, which submits biennial science indicators and science and engineering indicators, in accordance with Sec.4(J) of the National Science Foundation Act of 1950, to the president and Congress.

It is gratifying to read that UTEP is involved in the training of engineers who work for the factories located in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. This industry has grown to 3,500 plants along the 2,000-mile border that take advantage of cheaper labor in Mexico and the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA). UTEP has started a weekend graduate engineering program for advanced-level factory employees. About 100 engineers are participating.

Breaking Stereotypes

Hector De Jesús Ruiz, CEO of Advanced Micro Devices, is a Mexican-American engineer who represents the continuing change in our Mexican-American community. He was born in Piedras Negras, Mexico, and has a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. He

tells us that what helps him get through tough times is a memory from when he was 14 years old. He recalls that “a politician was on the radio proclaiming that he represented the party of the poor and the destitute. My father said, ‘Son, when you grow up, I don’t want you to be a member of a

party that caters to the oppressed and the poor. You have to aspire to be a member of a party that is happy, winning, and influential.’” Ruiz adds that the experience stuck with him and says that he does not want to be the underdog–he wants to try to figure out how he can win big.

Conversations Across the Border

During my last visit to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, I had the opportunity to visit a private college and prep school where my niece, Cecilia Valdez, is a teacher and administrator.

The campus is very modern, with some of the newest advances in technology that money can buy. At this institution, students are prepared for the job market in Mexico and in the U.S. The curriculum reflects both markets.

The school’s coordinator of international programs informed me that the school offers student exchange programs with Boston University, Purdue, University of British Columbia, and many other schools of higher learning throughout the world. The curriculum is accredited by the

Southwestern Association of Colleges and Universities. The coordinator told me that as many as 42 students transfer to the University of Texas at El Paso, located just across the border. The reasons for their transfer vary and include curriculum and finances. Some career tracks are not offered

at the college. Some students at the school are U. S. citizens and for them it is cheaper to attend UTEP.

I asked her about the factories along the border established through NAFTA, referred to in Mexico as “maquilas.” She told me that maquilas bring in their own professionals, according to the needs of each company. Obviously, they are a great source for all types of jobs along the border with Mexico. She had knowledge of a number of graduates who felt that there still exists prejudice against the foreign-born when applying for work in the U.S. The visa process is lengthy and costly. Her own brother, now working in Kentucky as an engineer for a Mexican company, would like to relocate in Mexico, she said.

During my visit, I also had the good fortune to talk with the coordinator of science programs for the college, who spoke about her very successful sons, both of whom work in the U.S. Her oldest earned his master’s degree from UTEP in engineering communications and studied his high school (preparatoria) in Mexico. He is now a successful design engineer in Newport Beach, Calif. Through his good academic record and teacher recommendations, he was able to qualify for a resident passport in the U.S. Her younger son was a business administration major at UTEP and earned an M.A. in accounting. He now works for El Paso Energy in Houston, Texas, and is married to a U.S. citizen, which allows him to file for his own U.S. residency.

In both situations, the quality of their lives in the U.S. far exceeds the one they would have experienced in Mexico, according to their mother. They are well adjusted to the competitive life in the U.S. and have proved that they can succeed in the U.S.

It is important to state that UTEP’s enrollment includes 1,749 students from Mexico, a 4 percent increase over last year. According to Natalicio, “These students represent approximately 15 percent of all Mexican nationals enrolled in the U.S. colleges and universities…”

Epilogue

I would like to encourage social researchers to separate data that refer to Mexican-Americans. It will help us assess the progress or lack of it of our Mexican-American community. Also, the persons who report the news in the media need to be more sensitive to patronizing and stereotyping.

My thanks to Walter Gilmore for his ideas, and to all the reference librarians at Sánchez Library, Pacifica, San Francisco State, and Skyline College. To all of you, a big Mexican hug.

References

Tyche Hendricks, “All Roads Lead to the Bay Area”, Associated Press, San Francisco Chronicle, Aug. 27, 2002, p. A12

Census Bureau SIC 926110, “Diversity of the Country’s Hispanics Highlighted in the U.S. Census Bureau Report, U.S. Newswire; March 6, 2001.

Pinto Alicea, Ines. Chapa, Flores, and Yzaguirre Press for Equity. Latino perspective on census 2000. Hispanic Outlook in Higher Education, Sept. 10, 2001 V.11; N.24 p 20.

Science and Engineering Indicators-2002. Vol. 2 p.A2-23 Garwood, Alfred. Hispanic Americans, a Statistical Sourcebook, published by Numbers and Concepts, 1991. Boulder, Colo. p. 132

US. Newswire, March 6, 2001.

Nova, UTEP Alumni Magazine. Winter 2002. p. 8

Lynn Elber, Associated Press, San Francisco Chronicle, Friday, Aug. 16,

2002, p. D 18.

San Francisco Chronicle, Aug. 27, 2002, p. A12

Susan Ferriss, American-Statesman International Staff, Austin American

Statesman; Austin, Texas; July 12, 2001, p.A4.

Ramona Ortega-Liston, “Mexican-American Professionals in Municipal Administration: Do They Really Lag Behind in Terms of Education, Seniority, and On-the-Job Training?” Public Personnel Management,

Summer 2001 V30 12 p. 197.

Science and Engineering Indicators-2002, Vol., 2, National Science Foundation, p.A169.

About the Author

Humberto Gutiérrez holds a B.A. in philosophy from UTEP, an M.A. in administration and supervision of education from CSU-Northridge, and was a doctoral candidate in both romance linguistics and philosophy of education at UCLA. His career in education spans three decades and includes teaching people of all ages, elementary and high school through college. He has developed and taught bilingual and multicultural programs at Mendocino College and throughout the L.A. Unified School District. Publications include Spanish for Our Schools and Spanish Developmental Reading Program, both for the L.A. City Schools, and Mexican-American History, for the Hispanic Urban Center.