Mexican American Fatherhood

M Culture – Counseling Fathers

… This chapter will outline several different areas relative to Mexican American fatherhood

to assist the counseling professional in develop- ing a deeper awareness of this population

and will propose culturally competent clinical interventions. …

Link to book

Medication administration hassles for Mexican American family caregivers

Abstract

In order to take their medications at home, elders rely increasingly on their family, but little is known about the factors influencing this task. This study explored the effects of acculturation and social exchange on the hassles that Mexican American (MA) family caregivers face in administering medication to their elders. A descriptive, correlational design, with a convenience sample of 239 MA adult caregivers of elders who were on a daily prescription that was recruited in Dallas, Texas and San Diego, California, USA, was used. The caregivers’ scores on the medication administration hassles scale were significantly affected by acculturation and social exchange factors that explained 36% of the variance in the scores; the social exchange block had a larger influence than did the acculturation block. Caregiving might be an outcome of dynamic family exchange relationships between the caregiving dyad. The results can help healthcare professionals to detect potentially at-risk MA families and provide them with culturally appropriate nursing interventions

Link to publication

Ethnicity in the Garden: Figurations of Ecopastoral in Mexican American Literature

D der Philosophie

Page 1. Ethnicity in the Garden: Figurations of Ecopastoral in Mexican American Literature

Inaugural-Dissertation … as well as in the introductions to the individual analytic main chapters.

Page 15. I. Towards a Theory of Mexican American Ecopastoral Page 16. Page 17. …

Mexican Business Organization Expands Its Focus

GlobalAtlanta

Speaking to an audience of 35 business professionals at a breakfast meeting on March 17 at the Goodwill Northeast Plaza Career Center, Alejandro Coss, president of the Mexican American Business Chamber, announced the new partnership.

“Hay Que Ponerse en los Zapatos del joven”: Adaptive Parenting of Adolescent Children Among Mexican-American Parents Residing in a Dangerous Neighborhood

M CRUZ‐SANTIAGO, G RAMÍREZ… – Family Process, 2011

… “Hay Que Ponerse en los Zapatos del Joven”: Adaptive Parenting of Adolescent Children

Among Mexican-American Parents Residing in a Dangerous Neighborhood. … All participants

were born in Mexico and identified as Mexican or Mexican American. …

The Mexican American Second Generation in Census 2,000

J Perlmann – The Next Generation: Immigrant Youth in a …, 2011

… It does not follow, however, that Mexican American patterns will parallel those of the European

immigrant past—if by that we mean … widening gap between the minimally paid menial jobs that

immigrants commonly accept and the high-tech and professional occupations requiring …

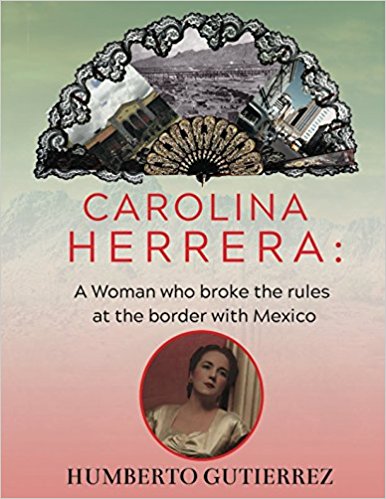

Mexican census 2010: Languages other than Spanish spoken in Mexico

H. Gutierrez

There are close to 7,000,000 Mexicans who speak languages other than Spanish in Mexico. You will observe that the numbers of native speakers of other languages have grown according to the last census.

Validating the Mexican American Intergenerational Caregiving

S Escandón – The Qualitative Report, 2011

… The purpose of this study was to substantiate and further develop a previously formulated

conceptual model of Role Acceptance in Mexican American family caregivers … In addition, results

inform health professionals about the ways in which Hispanic caregivers view caregiving. …

The Meaning of Numbers in Health: Exploring Health Numeracy in a Mexican-American Population

Marilyn M. Schapira, Kathlyn E. Fletcher, Pamela S. Ganschow, Cindy M. Walker, Bruce Tyler, Sam Del Pozo, Carrie Schauer and Elizabeth A. Jacobs

Original Research

The Meaning of Numbers in Health: Exploring Health Numeracy in a Mexican-American Population

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Health numeracy can be defined as the ability to use numeric information in the context of health. The interpretation and application of numbers in health may vary across cultural groups.

OBJECTIVE

To explore the construct of health numeracy among persons who identify as Mexican American.

DESIGN

Qualitative focus group study. Groups were stratified by preferred language and level of education. Audio-recordings were transcribed and Spanish groups (n = 3) translated to English. An analysis was conducted using principles of grounded theory.

PARTICIPANTS

A purposeful sample of participants from clinical and community sites in the Milwaukee and Chicago metropolitan areas.

MAIN MEASURES

A theoretical framework of health numeracy was developed based upon categories and major themes that emerged from the analysis.

KEY RESULTS

Six focus groups were conducted with 50 participants. Initial agreement in coding was 59–67% with 100% reached after reconciliation by the coding team. Three major themes emerged: 1) numeracy skills are applied to a broad range of communication and decision making tasks in health, 2) affective and cognitive responses to numeric information influence use of numbers in the health setting, and 3) there exists a strong desire to understand the meaning behind numbers used in health. The findings informed a theoretical framework of health numeracy.

CONCLUSIONS

Numbers are important across a range of skills and applications in health in a sample of an urban Mexican-American population. This study expands previous work that strives to understand the application of numeric skills to medical decision making and health behaviors

Link to abstract

Forty years later, the contraversy over journalist Ruben Zalazar’s…

By Leslie Berestein Rojas

I was a young Mexican-American in 1970 and remember these events very well. I followed the event and the story for forty years. I cannot under my professional opinion believe & will ever believe that LASD and it’s Deputies involved in …

Modern Language Association enrollments in foreign languages.

Dec 8, 2010 … Fall enrollments for 2009, released today by the Modern Language Association shows increased enrollments ..

Ghostly (I)s/:The Formation of Subjectivity in Mexican American Life Narratives

PM Perea – 2011

… Until my first semester in Professor Limón’s graduate seminar, I had no idea Mexican American

literature existed. … Page 7. vii Page 8. viii GHOSTLY I(S)/EYES: THE FORMATION OF

SUBJECTIVITY IN MEXICAN AMERICAN LIFE NARRATIVES by Patricia Marie Perea …

Mexican American and Immigrant poverty in the United States

G. Garcia – 2011

… and health care applications • Methods and estimates for unique populations such as schools

and students Volumes in the series are of interest to researchers, professionals, and students …

Ginny Garcia Mexican American and Immigrant Poverty in the United States 123 Page 5. …

Oportunidades Educacionales para Mexicanos en el exterior

Educación

El IME busca contribuir al desarrollo individual y colectivo de la población mexicana y de origen mexicano en el exterior, a través de la promoción de programas de educación formal e informal, en colaboración con diversas instituciones educativas en México, Estados Unidos y otras regiones del mundo.

En este sentido, se impulsan diferentes iniciativas en materia educativa, mismas que se presentan en 7 grandes rubros, para su fácil consulta.

Educación Superior

Educación virtual y a distancia

Educación para jóvenes y adultos

SEP – Programas específicos de colaboración

Programa Binacional de Educación Migrantes (PROBEM)

Otros programas en beneficio de la comunidad en el exterior

Convocatorias 2009

Impartirán inglés desde preescolar hasta secundaria en la entidad, anuncia Educación y Cultura

Erika Talina Perea

El Diario | 26-01-2011 | 00:44

Chihuahua— Niños desde preescolar hasta nivel medio superior aprenderán el idioma inglés como segunda lengua anunció la Secretaria de Educación, Cultura y Deporte en el marco de la firma del Convenio Educativo con el Consulado de Estados Unidos.

El director de Educación Superior, Carlos Ochoa Ortega expresó que es importante que se fortalezca el idioma inglés entre los niños chihuahuenses para que en un futuro puedan acceder a los programas de intercambio estudiantil y cultural que existe con la Unión Americana.

Y anunció que a partir de este año se instrumentarán los mecanismos para que los maestros de distintos niveles educativos tomen un curso intensivo de inglés para enseñarlo a sus alumnos.

“En lo que a mi área corresponde estaré platicando con directores e inspectores de educación media superior y superior para que seleccionen a un grupo de maestros y los enviemos a estudiar inglés una temporada a Estados Unidos”.

Agregó que se pretende sumar a este proyecto a los niveles de educación básica desde preescolar, primaria y secundaria pues entre más pequeño es el niño puede aprender la segunda lengua con mayor facilidad.

Esto derivado del convenio de entendimiento que ayer martes signó la Secretaria de Educación y Cultura para promover el Centro de Asesoria Education USA.

El Centro de Asesoría Educativa Education USA es un organismo que ofrece a los interesados información sobre opciones y oportunidades educativas en todas las instituciones acreditadas de educación superior en Estados Unidos.

Al respecto el subsecretario de la SECD señaló que para el estado de Chihuahua es una distinción contar en la ciudad de Chihuahua con dos centros de este tipo; uno en Juárez y el nuevo que estará funcionando en la capital del estado, pues en todo el mundo funcionan 420 instituciones similares, promovidas por el gobierno norteamericano.

Señaló que en nuestro país las instituciones de educación superior “significan un factor de movilidad social que nosotros tenemos que impulsar”.

CARTA A UN MAESTRO

Creo que ser maestro tiene, como la Luna, se cara luminosa y su cara oscura. En la vida casi todo es así; no hay nada tan malo que no tenga algo bueno y al revés. Lo que importan es ser consciente de todo, luces y sombras, para que nada nos tome desprevenidos y sobre aviso no hay engaño. No abogo por una actitud estoica ante la ambivalencia de la vida, ni mucho menos por la resignación; más bien por una actitud realista que relativice lo negativo y valore sin fantasías los positivo; creo que por ahí va eso que llaman madurez.

El lado oscuro de la luna lo conoces bien. Es el bajo suelo, y más fondo, lo que ese suelo significa: el poco reconocimiento social hacia el maestro. Esto duele; lo percibes todos los días y te acompaña como mala sombre; a veces alguien te ve de arriba abajo; mucha gente no valora lo que estudiaste ni lo que haces. El lado oscuro son también los escasos recursos con que cuentas para realizar tu tarea y l apoca atención que les mereces a las autoridades. Fuera del libro de texto y el gis, casi no cuentas con nada; estás liberado a tu imaginación.

Hay, además, corrupción en el medio magisterial; reglas de juego poco edificantes que tienes que aceptar; a veces la manipulación, abusos y un doble lenguaje que molesta, hay también – aun que no es privativo de tu profesión- rivalidades, murmuraciones, envidias y zancadillas de algunos compañeros. Entre esto hay que caminar, como equilibrista sobre la cuerda floja.

Júntale a todo lo anterior la pobreza de los alumnos que se les dificulta tanto aprender; la testarudez, indisciplina y rebeldía de algunos muchachos del aula; la ignorancia, a veces, de los padre de familia que no saben cómo estimularlos ni corregirlos, y la maledicencia, que nunca falta, en la comunidad. Para ganarte la atención de los chicos tienes que competir con la “tele”, los videos y los cantantes de moda, en batallas que estar perdidas de antemano; y como colofón, se te culpa no solo de que los alumnos no aprendan, sino de todos los males del sistema educativo. Decididamente, el lado oscuro es más bien negro, de tantas dificultades y problemas que tiene la profesión.

Que podremos en el lado luminoso? Yo fui maestro por varios años (un tiempo quizá demasiado corto para tanto como ahora hablo sobre la educación) y recuerdo siempre tres cosas que me parecen hermosas y hoy añoro.

La primera es la experiencia de “ver aprender”, suena curioso decirlo así pero no hallo otra manera. Aunque daba clases en una secundaria. Por una circunstancia excepcional me tocó en unas vacaciones ensenar a leer a varios niños; en otra época posterior ensene a leer a un grupo de campesinos adultos ( uno de ellos, don José, de 76 años, por cierto) en el momento en que las letras se convierten en palabras y estas en pensamientos es como un chispazo que estremece al niño y al adulto por igual; en ese momento el niño sonríe y su sonrisa es expresión de triunfo, gozo de descubrimiento y juego ganado; el adulto es emoción que le desconcierta, comprobación de que “no era tan fácil” y extraña sensación de descubrir que el pensamiento está escondido en los garabatos del papel. Yo simplemente lloré cuando don José me dijo esa tarde: “Ya sé leer; y estoy gente de razón”, soltando un orgullo reprimido por setenta años.

Ver aprender, presenciarlo, mas cómo testigo que como actor, es la satisfacción fundamental de quien enseña. Lo malo está en que a veces nos concentramos en vez de disfrutar el milagro continuo de los que aprender. Ver aprender es ver crecer y madurar a los niños y jóvenes, comprobar por sí mismos y que van saliendo adelante.

Mi segundo recuerdo se liga a la formación de carácter de mis alumnos adolescentes. Siempre considero esto tan importante o más que el que aprendieran conocimientos. Una vez el grupo de tercero de secundaria debía organizar una serie de festejos y el director me encargó de coordinar las actividades. Propuse a la clase que tomáramos esa experiencia como una ocasión para que cada uno conociese mejor sus cualidades y sus defectos y la manera en la que los demás los percibían. Establecimos por conceso los “criterios de evaluación” (compañerismo, creatividad, eficiencia, y ano recuerdo, eran como diez) y después de los festejos, el grupo evalúo a cada alumno a la luz de esos criterios. Hoy, muchos años después, cuando me encuentro a alguno de aquellos muchachos, me dicen: “maestro, esa experiencia fue para mí definitiva; ahí empecé a conocerme de veras; fue estupendo.”

Ser maestro o maestra es ser invitado, en ciertos momentos privilegiados, a entrar al alma de un chico o una chica y ayudarle a encontrarse, a firmar paulatinamente su carácter, a descubrir sus emociones, quizás a superar sus temores y angustias. Y para muchos alumnos o alumnas el maestro o la maestra son los únicos apoyos con los que cuentan.

El tercer recuerdo de esos años, que hoy evoco con nostalgia, es que el contacto cotidiano con los alumnos me mantenía joven. Tus alumnos te obligan a estar enterado de cuanto pasa; te bombardean con preguntas; te ponen en órbita; de todo tienes que saber; acaban ensenándote mas que tú a ellos. Esto es bonito: ser maestro es seguir creciendo.

Evoco hoy estos recuerdos que son, para mí, algunos atisbos del lado luminoso de la Luna. Otros maestros, tú mismo, añadirías mas luces con el lenguaje insustituible de tu experiencia de vida. Si en el balance final las luces son más poderosas que las sombras, no lo sé. Es cosa de vocación, de inclinación interior, de proyecto de vida. O quizá de amor. Y digo la palabra sin ruborizarme porque creo que la profesión de maestro se emparenta con la paternidad y ésta o es amor o no es nada. Todo hijo causa muchos problemas, desde los biberones y panales, pasando por los médicos, hasta los inevitables desencuentros de la adolescencia; pero ningún padre ni ninguna madre pone en duda que en cada hijo las luces superan a las sombras.

Si tienes vocación de maestro, concluyo, creo que tú también opinarás, sin grandilocuencia ni idealizaciones, que la Luna es, decididamente, luminosa y bella.

¡Felicidades maestro!

——————————————————————————–

Comentarios

nombre:

email:

comentario:

——————————————————————————–

Aún no existen comentarios. Se el primero!!!

desarrollado por www.newdiscoverymedia

LA EVALUACIÓN DEL MAGISTERIO

Sorprende la cifra recabada por la Secretaría de Educación Pública sobre todo porque la evaluación era un requisito, supuestamente indispensable, para que los maestros recibieran estímulos de hasta 150% de su sueldo. Esta anomalía nos puede hacer especular varias cosas. O los profesores nunca se enteraron de la opción, o no necesitan el incremento, o han conseguido recibirlo a través de otros canales, o tienen más razones para negarse a ser evaluados de las que tienen para realizar el trámite. Por los resultados de este examen, la respuesta parece ser la última, si bien tal vez no es la única

El Programa Internacional para la Evaluación de Estudiantes (PISA por sus siglas en inglés) por citar la más reconocida de las mediciones educativas, no examina la calidad de los maestros, pero sí la de sus resultados. Dicha prueba ha demostrado año con año que México está por debajo del nivel educativo del resto de los países de la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. ¿Esto qué significa?

A la larga, como lo ha demostrado la historia, son los países con generaciones mejor preparadas los que hacen crecer su economía e incrementan la calidad de vida de sus habitantes. Corea del Sur y Japón son un ejemplo consolidado de cómo aprovechar en ese sentido la ciencia y la tecnología. Hacia allá se dirigen a últimas fechas países como China e India, incluso Brasil a pesar de que sus indicadores educativos son similares a los de México.

Cambiar el hecho de que nuestro país exporte frutas y maquila en vez de barcos o computadores depende en primera instancia de la educación. Llegar a ser parte de la sociedad del conocimiento tiene como primer paso diagnosticar adecuadamente los recursos educativos. Eso incluye a los maestros.

Los recursos naturales y la mano de obra barata para la exportación ya no pueden sostener más los privilegios acumulados. Hay que apoyar a los profesores, como a todos, en proporción a la calidad de su trabajo.

Fuente: Educación a Debate

——————————————————————————–

Comentarios

nombre:

email:

comentario:

——————————————————————————–

Aún no existen comentarios. Se el primero!!!

Research Briefs Cervical Cancer Screening and Older Mexican American Women: A Case Study

Research in Gerontological Nursing Vol. 4 No. 1 January 2011

By Bertha “Penny” Flores, MSN, RN, WHNP-BC; Deborah L. Volker, PhD, RN, AOCN

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to explore an older Mexican American woman’s decision-making process to engage in cervical cancer screening. A qualitative single case study design was used along with a purposive, typical case sampling strategy. The participant, a 52-year-old Mexican American woman, was interviewed using a semi-structured format. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the data. The analytic process revealed three concepts and motivators that influenced the participant’s behavior regarding cervical cancer screening practices: knowledge, family history, and sexual history. As such, these findings are useful for crafting subsequent investigations. Although the study participant’s experience is instructive regarding facilitators or motivators for engaging in screening practices, further exploration of barriers faced by older Mexican American women who decline to be screened is warranted.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ms. Flores is Clinical Assistant Professor, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, and a 2009-2011 John A. Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Scholar and a doctoral student, The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing, and Dr. Volker is Associate Professor, The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing, Austin, Texas.

The authors disclose that they have no significant financial interests in any product or class of products discussed directly or indirectly in this activity. The authors acknowledge support from the John A. Hartford Foundation for Bertha “Penny” Flores.

Address correspondence to Bertha “Penny” Flores, MSN, RN, WHNP-BC, Clinical Assistant Professor, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229; e-mail: Floresb2@uthscsa.edu.

Received: July 20, 2010; Accepted: October 27, 2010; Posted: December 29, 2010

doi:10.3928/19404921-20101201-04

México con 33 millones en rezago educativo

Domingo 02 de enero de 2011

Nurit Martínez | El Universal

nurit.martinez@eluniversal.com.mx

24 comentarios

En México, cuatro de cada 10 personas mayores de 15 años están en situación de “rezago educativo”, esto es que no concluyeron estudios de educación básica: son analfabetas, no terminaron la primaria o la secundaria y esa situación los hace enfrentarse en condiciones de desventaja en el mercado laboral, con ingresos promedios de entre seis y ocho pesos por hora laborada, mientras que una persona que alcanza estudios universitarios logra ingresos de 56 pesos la hora, según estimaciones de la Secretaría de Educación Pública.

El número de mexicanos con capacidades mínimas de educación se incrementó más de 3.6 millones de personas en las últimas dos décadas, al pasar de 29.7 millones a 33.4 millones, informó el Instituto Nacional de Educación para los Adultos.

El que no sepan leer y escribir o que no hayan terminado la primaria o la secundaria significa que enfrentan mayores posibilidades de estar desempleados, recibir bajos salarios o trabajar sin prestaciones y también carecen de conocimientos mínimos para procurarse formas de vida saludables como elegir alimentos al comprarlos, lavarse las manos, los dientes o hervir el agua.

Lograr estudios de nivel básico hace que aumente el interés por mantenerse informados sobre asuntos políticos y encontrar soluciones a conflictos de su entorno inmediato, refiere la Evaluación de Impacto del Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo realizado por Investigaciones Sociales, Políticas y de Opinión Pública solicitada por el INEA.

“Es una desventaja educativa para la empleabilidad y hace que cuando logran su inserción laboral, sea en el mercado informal o en actividades como la delincuencia organizada y esto último es lo que debería llamar la atención más allá de los discursos”, asegura Roberto Rodríguez Gómez, miembro del Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

Lo que más preocupa a la SEP es que 44% de los 33 millones 403 mil personas en rezago tienen entre 15 y 39 años de edad.

El último reporte del INEA refiere que existen seis millones de mexicanos en condición de analfabetismo, 10 millones más que no concluyeron la primaria y otros 17 millones de jóvenes y adultos que truncaron sus estudios en la secundaria.

Si bien el número de analfabetas en el país se mantiene en torno a los seis millones de personas desde la década de los 70, el grupo de personas que no concluyeron la secundaria sumaron más de 2 millones 680 mil personas, según las cifras de rezago educativo.

Para disminuir este problema, el secretario de Educación Pública, Alonso Lujambio, anunció que a la par de que se realizará la preinscripción de niños a la educación básica, se levantará un primer censo nacional de escolaridad de los padres de familia para “promover que quienes no hayan concluido la primaria o la secundaria, o incluso que no sepan leer o escribir, puedan retomar los estudios y concluyan su educación básica”.

Lujambio Irazábal convocó a los gobiernos estatales para que en 2011 se pueda concretar una estrategia nacional para la retención y la no reprobación de los alumnos de secundaria.

El estudio “El analfabetismo en América Latina una deuda social”, elaborado por el Sistema de Información de Tendencias Educativas en América Latina, del Instituto Internacional de Planeamiento de la Educación, estima que en México la desigualdad en el acceso de oportunidades educativas hace que existan tres analfabetas en zonas rurales por uno en las zonas urbanas.

“El número de personas adultas que carecen de competencias mínimas necesarias en escritura, lectura y cálculo elemental se torna en un indicador crítico de la situación de inequidad existente en Latinoamérica y en una evidencia de la deuda que todavía tienen los Estados y el conjunto de la sociedad con una importante parte de ella”, señala el informe.

Con base en un diagnóstico de la Subsecretaría de Educación Básica, se estima que un millón 200 mil adolescentes reprueban o abandonan la escuela en ese nivel educativo cada año.

Es con un grupo de ellos y de los que abandonan o reprueban la primaria, que el INEA recibe cada año a 630 mil niños y jóvenes que se suman al “rezago educativo fresco”, reconoce el Instituto.

Para el especialista Roberto Rodríguez Gómez, el gobierno “no está a la altura de la problemática, sus acciones son deficientes y pobres a lo largo de la historia la alfabetización, sólo ha formado parte de la liberación del servicio militar obligatorio o del servicio social de algunas universidades”.

El rezago educativo en México “requiere que se le dé prioridad, atención y eso se refleje en el dinero que se le destina. Emprender una acción de este tipo podría ofrecer, incluso, oportunidades de empleo a los jóvenes y el alfabetizador sería un profesional y no una labor altruista”.

El INEA señala que el promedio nacional del costo por alumno es de 5 mil 400 pesos, pero varía de una entidad a otra.

TechnoratiFacebookTwitterYahooGoogleCompartir

Para comentar,

Iniciar Sesión o Regístrate

24 Comentarios

Mostrar: Recientes | Polémicos | Votados

Sólo se permitirán participaciones con menos de 500 caracteres.

Comentarios: 1 – 20 Ver más comentarios >>

REPORTA ABUSO Este espacio es regulado por la propia comunidad. ¿Crees que el comentario, avatar o imagen que lo acompaña son inapropiados? REPÓRTALO

(Con cinco reportes el post será eliminado automáticamente)

Serv D.F. 02 de enero del 2011 13:43 Y gracias a medios que aplauden todo lo que dice el gobierno por no perder el ingreso de la publicidad gubernamental el país esta como esta ahora resulta que nadie es cómplice del mal gobierno!

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso Allbert13579 Vancouver 02 de enero del 2011 13:38 Despiertate censor!!!!!!! andas crudo todavia????

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso Allbert13579 Vancouver 02 de enero del 2011 13:34 Y todavia nos sorprendemos de los niveles de pobreza, violencia y corrupcion.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso PERDURABO DISTRITO FEDERAL 02 de enero del 2011 13:32 Y el Sindicato? pues repartiendo Hummers y madreando granaderos. Es mas que claro que el sistema educativo no funciona tanto gubernamental como el que prevalece en la casa, para que una mejóría se de alguien debe tomar la iniciativa en la SEP y con una estrategia clara, quien será?. Y para los que son adultos y tienen conciencia de su situación hay formas para estudiar algo y mejorar la calidad de vida.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso vicunca Riga 02 de enero del 2011 13:31 Los países títeres siempre tienen a su población pobre y casi sin educación. Son países destinados a generar mano de obra barata para otros países. Mientras no se genere educación de calidad en este país, seguiremos siendo el segundo país en el mundo con mas ciudadanos viendo afuera de las fronteras. Muchas veces en condición de esclavos.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso

jieg Df 02 de enero del 2011 13:31 lo patetico de este rezago educativo, es que si le preguntan a cada gobernador, estos inutiles diran que su estado es campeon en educación a nivel nacional, pero los numeros de los gobernadores siempre son mentiras

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso ellaestere Priespeligropanesmuerteprdesbasura 02 de enero del 2011 13:29 esperare pacientemente a que permitan publicar un comentario

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso autenticcamaleon D.F 02 de enero del 2011 13:21 no hay necesidad de leer el articulo, ya que esto se compensa con el doble de narcos, comerciantes, etc. que no requiren estudos para ser exitosos en la vida, y tener dinero más que suficiente.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso eltata Tijuana 02 de enero del 2011 13:03 Por todo esto y mucho mas… gracias a la vitalicia de ELba Esther Gordillo. Obstaculo de la educacion publica.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso KRISTIAN CApital DF 02 de enero del 2011 12:51 a quien hay q culpar?

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso

cuchillo MEXICO 02 de enero del 2011 12:49 La información económica está a medias, en realidad un albañil con 1o de primaria puede ganar más que un ejecutivo de cuenta de un banco (por más bonitas que estén). Se privilegia más al esfuerzo físico que al conocimiento en algunos casos.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso Montalbo El cerrito 02 de enero del 2011 12:40 Hen mejiko no ai HA NALFAVETAZ zi todoz bemos el progrmah ece de la profe gordiyo en la TB…HA NALFAVETAZ zu avuela!!!

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso Fredy68 Valle de chalco 02 de enero del 2011 12:28 Des-afortunadamente con los gobiernos del PAN la educación, el poder adquisitivo del salario y el desarrollo se han venido abajo. el fracaso no es sino resultado de los gobernantes me/dio/cres que no saben gobernar.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso alternativa1 Tampico 02 de enero del 2011 12:27 CON EL NARCO PAN…MEXICO REZAGADO….PARA VIVIR MEJOR…REZAGADO…

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso Elbarbaazul Monterrey 02 de enero del 2011 11:52 PARA VIVIR MEJOR ! !

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso

beatrix PLEASANTON 02 de enero del 2011 11:42 Una reforma educativa en la formacion de Maestros academicos y profesores. asi mismo en las escuelas.. Muchos de estos personas son las que emigran a USA por falta de oportunidades y aqui encuentran el paraiso al no pedirles escolaridad . cuando este pais se las pida dejaran de venir a mendingar . 200 anos de Independencia y no ha servido para mejorar la educacion que es la base del progreso de un Pais . Comparen con Finlandia 93 anos de independecia y 1Er lugar de esducacion en el mundo

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso velaturbo Los Mochis 02 de enero del 2011 11:41 LAMENTABLE, SIGUEN FALLANDO LAS POLÍTICAS EDUCATIVAS Y SOCIALES EN MÉXICO,URGE CAMBIARLAS Y COOPERAR TODOS LOS MEXICANOS. LA CLASE POLÍTICA SIGUE DESORIENTADA, PERDIDA, LAMENTABLE. GRACIAS Y SALUDOS!

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso ingaquedito Estado Fallido del yo porque y del haiga sido 02 de enero del 2011 11:37 Esas cuatro de cada 10 personas mayores de 15 años que son analfabetas o no concluyeron estudios de educación básica que ni se preocupen, arrimense a algun partido politico ande de arrastrados y abrepuertas un rato y seguro buena chamba en el gobierno agarran.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso Fulcrom D.F 02 de enero del 2011 11:20 Como país gastamos millones y millones en salarios de profesores desde hace lustros y no se ve claro si esos gastos redituan. Especialmente en las zonas rurales.

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso igalil Mexico 02 de enero del 2011 10:26 ¿Nomas en educación? creo que tiene otrs 70 millones con rezago economico y social…

Me gusta (0) No me gusta (0) Responder Reportar abuso

Para comentar,

Iniciar Sesión o Regístrate

Crea comunidad. Comenta, analiza, critica de manera seria. Mensajes con contenido vulgar, difamatorio o que no tenga que ver con el tema, serán eliminados. Sólo se permitirán participaciones con menos de 500 caracteres.

Lee las normas | Políticas de uso | Políticas de privacidad

Mostrar: Recientes | Polémicos | Votados

Sólo se permitirán participaciones con menos de 500 caracteres.

Comentarios: 1 – 20 Ver más comentarios >>

REPORTA ABUSO Este espacio es regulado por la propia comunidad. ¿Crees que el comentario, avatar o imagen que lo acompaña son inapropiados? REPÓRTALO

(Con cinco reportes el post será eliminado automáticamente)

Las MásLeídas

Enviadas

Comentadas

Kalimba ingresa a Cereso de Chetumal

Acostumbrada a los desnudos en el cine

Se suicida mamá de modelo muerta por anorexia

Megan Fox, ¿demasiado esbelta?

Katia D Artigues Las búsquedas de la PGR • Peleas electoralesCocina al natural: pastel alemánSaca provecho de la crisis en EuropaCae red de pornografía infantil que usaba Twitter y Facebook15 meses sin lavar pantalones no trae consecuenciasSe suicida mamá de modelo muerta por anorexia

Megan Fox, ¿demasiado esbelta?Kalimba ingresa a Cereso de ChetumalCalderón pide cuidar lo que se dice del paísFederales repelen ataque en hotel de NLMalas noticias tienen efecto demoledor: FCH

http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/notas/734432.html

Issues in Mexican American Education: Addressing the Academic Needs of Mexican American Students at the Secondary Level

| Author: | Alvarez, Ricky A |

| Abstract: | In light of the growing number of ethnic minority adolescents in the United States, it has long been recognized that the level of educational attainment of Mexican-American students is below to that of other ethnic minority communities in the United States. From towering impoverishment rates, lower parental education, dilapidated neighborhoods and communities, to a clash of culture, marginalized education, and impersonal behaviors, Mexican-American students have endured an educational challenge that has become more difficult to win than imagined. Entailed by cultural identity, exceptionalities, language, gender, economic status, health, beliefs, values, and perceptions of education, this thesis will not only make possible recommendations for the plight among Mexican-American education, but will also investigate the socioeconomic, sociocultural, and the supplementary issues and factors that influence the academic advancement of Mexican-American students at the secondary level. |